The problem with false feminism

(or why ''Frozen'' left me cold)

The problem with false feminism

(or why ''Frozen'' left me cold)

I have made absolutely no secret of how much I disliked Disney's Frozen. I hated it. I spent most of the movie alternately facepalming, groaning, and checking my watch, and when people asked me how I liked it, I made this face:

As far as I could see, the problems were obvious. Just like The Princess and the Frog, I felt like Disney had started with some admirable intentions, but lost their gumption halfway through and covered up with cheap storytelling tricks and a lot of audience pandering. And when I told people how I felt about The Princess and the Frog (and Brave, for that matter-but we'll get to that), they mostly agreed with me. I don't make a habit of dogmatically disliking something just because I feel like it: usually if I have a viscerally negative reaction to a film, there's a healthy contingent of people out there who have the same reaction for much the same reasons.

It was, therefore, a huge surprise to me just how many people loved Frozen. Not just loved, but slavered over it. Critics have been downright competitive in their effusiveness, calling it ''the best Disney film since The Lion King'', and ''a new Disney classic''. Bloggers and reviewers alike are lauding it as ''feminist'', ''revolutionary'', ''subversive'' and a hundred other buzzwords that make it sound as though Frozen has done for female characters what Brokeback Mountain did for gay cowboys. And after reading glowing review after glowing review, taking careful assessment of all the points made, and some very deep navel-gazing about my own thoughts on the subject, I find one question persists:

Were we even watching the same film?

Everyone's entitled to their opinion. I certainly love some movies other people loathed; I'll even be referring to one of them in a few paragraphs. If your reason for liking Frozen is that it's fun, or the songs are catchy, or the animation is beautiful, or Olaf the Snowman is funny, then more power to you. But if you like Frozen because you think it is some revolutionary step forward in the way animated films portray women, then I think you're wrong. And unfortunately, when it comes to film's historically awful track record for portraying, hiring and being remotely fair to women, celebrating the wrong film-particularly in the sheer numbers that people are celebrating Frozen-has some very troublesome implications.

My friends have asked for it and I feel like the internet needs it, so I'm going to go through, point-by-point and in no particular order, the top handful of reasons people have given for thinking Frozen is a feminist triumph, and I'm going to debunk them all.

Here goes.

There was no wedding at the end of the film.

I've heard a lot of people trumpet the fact that no one ended up married as some great progressive anomaly for Disney. The formula as we know it is so ingrained we don't even have to think. Whatever the heroine's dream, at some point she meets a man who helps her on her way, and the two fall in love just convincingly enough for the film to end on a shot of her in a giant meringue of a gown while bells ring and a carriage with ''Just Married'' on the back is driven away by a dozen white horses. But in Frozen, the man Anna decides she's going to marry in the first few minutes turns out to be a cad, and her relationship with her other love interest ends at their first kiss. It would be a sort-of-compelling argument, if it were true.

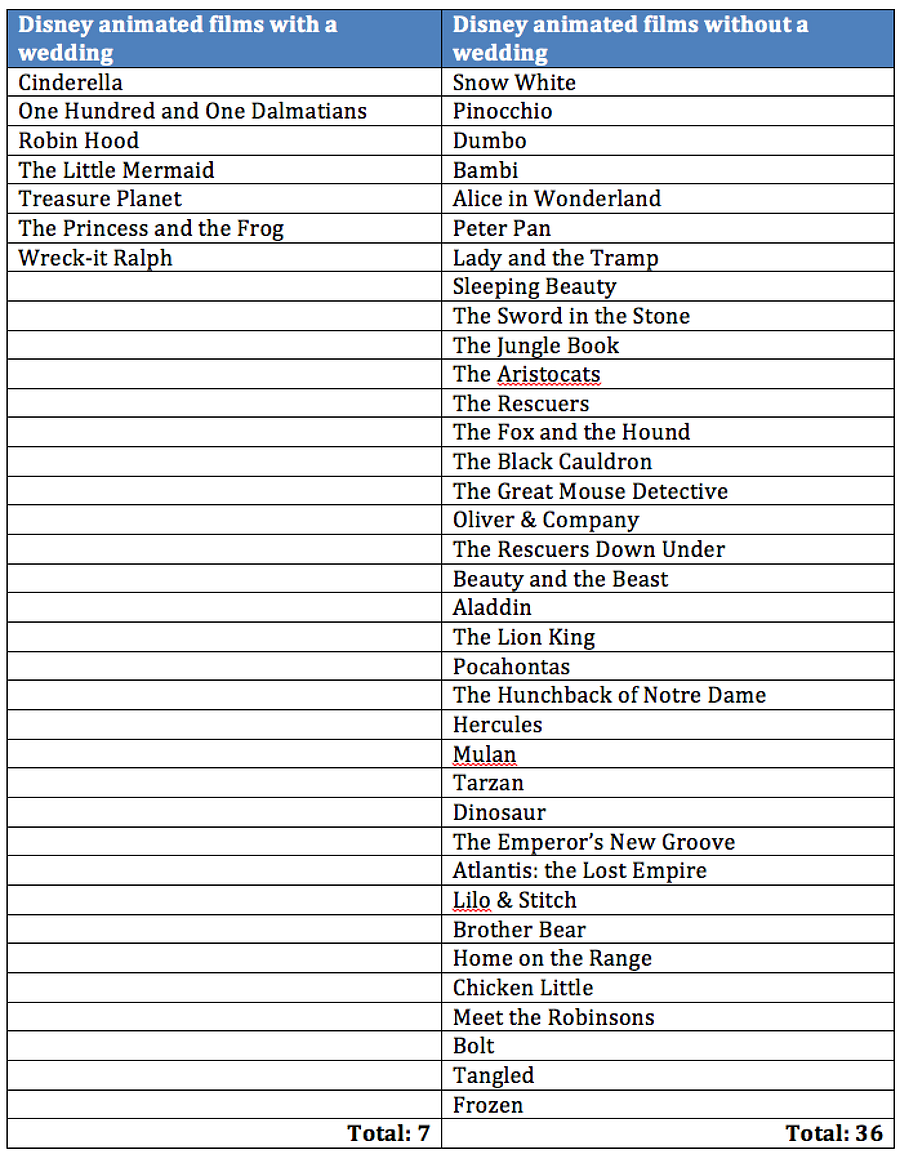

In the interest of absolute fairness, I did some digging. Of the 43 feature-length theatrical animated films Disney has produced-so, not counting Pixar films, anthology films (like Winnie the Pooh or Fantasia), direct-to-video sequels or films produced by other studios and distributed by Disney-how many do you think feature a wedding between anyone? Main characters, loveable sidekicks or one-scene supporting characters? All of them?

Seven. Seven Disney films show a wedding on-screen, or feature two characters getting married within the timeline of the movie. Here's the table to prove it:

Surprising, isn't it? With the number of animal features to account for, you'd expect a bit of an imbalance, but the wedding-less features outnumber the ones with church bells by a shocking five to one. Snow White? No marriage, no betrothal; she just hops on the prince's horse and rides off with him. Sleeping Beauty? They dance and her dress changes colour. Beauty and the Beast ends with the exact same dance scene as Sleeping Beauty, and Pocahontas watches her beloved sail back to England.

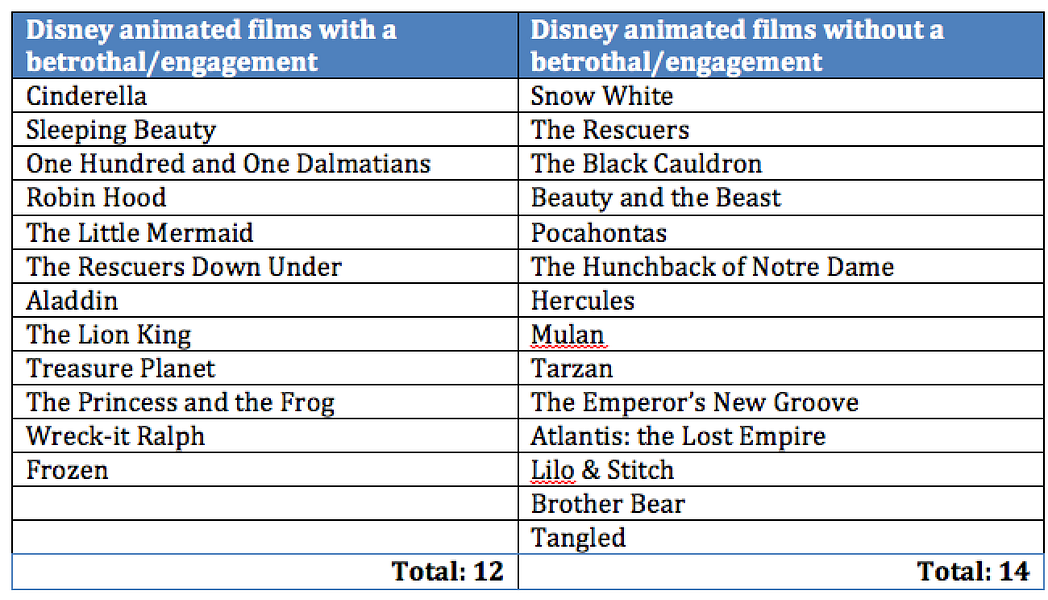

To even the playing field, let's remove the completely irrelevant movies, by which I mean the ones that involve non-anthropomorphic animals, protagonists too young for a love interest, and the ones that are so godawful we all prefer to pretend they don't exist. I'm also broadening my definition of the Disney formula to include betrothals and engagements as well as weddings:

There are a couple of things of note here. Firstly, while it's a much more even distribution, the engagement-free films still outnumber the films with engagements or betrothals, and it certainly isn't nearly as heavily weighted towards betrothals as you'd expect. Secondly, look where Frozen ends up. It may ultimately be to the wrong guy, but Anna does spend most of the movie engaged, and that's important for two reasons: first, that if you count Aurora's betrothal to Phillip in Sleeping Beauty and I know you do, despite that it happens when they're both infants and the fact that she falls in love with Phillip while disguised as a peasant is a total coincidence-then to be fair, you have to count Anna's engagement to Hans. Second ...well, we'll get to that later, but for now let's say that Anna's engagement is significant to her, so it should be to us as well.

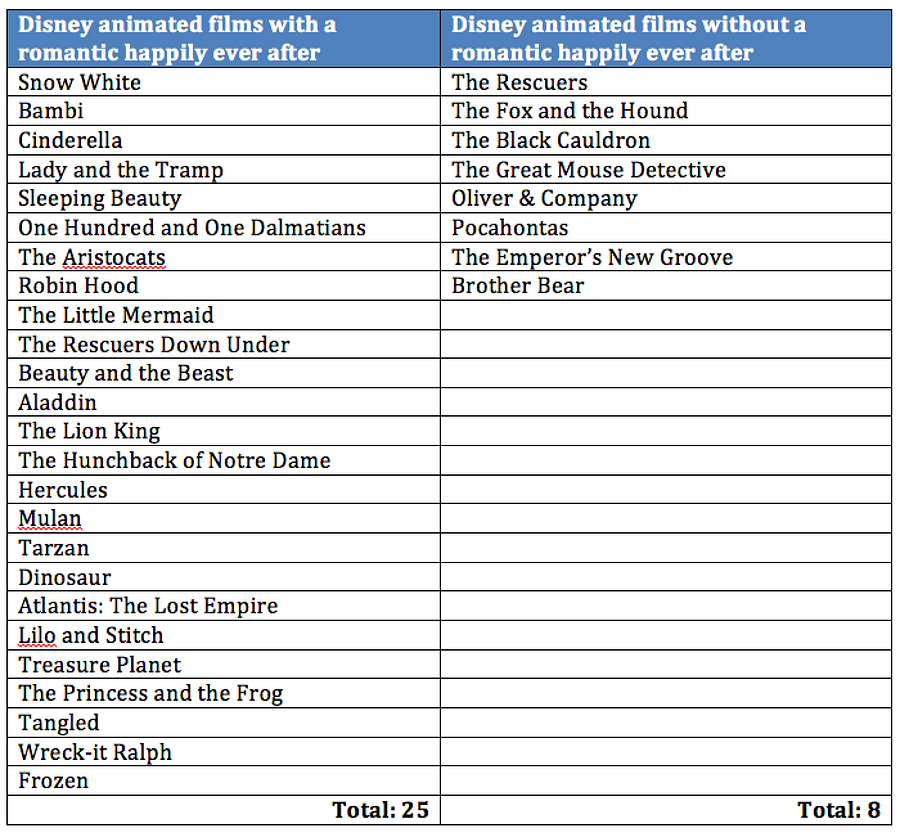

In the interest of weighting this as far towards the perceived Disney mould as possible, I have one more table for you. In this one, I've put the animal features back in, and I'm now counting out every feature with a love story that ends in a happily ever after. A traditional, heterosexual happily ever after, I should qualify, though it's not like Disney is likely to actually attempt a same-sex love story any time soon. Or ever. Here's how that one tallies up:

I would like to point out that I'm being really generous here. In the happily-ever-after column I've included multiple supporting character romances and a couple of really questionable selections (Simba's romantic relationship with Nala is just about the least important part of the climax of The Lion King, in Lilo and Stitch it's never clear whether Nani and David become more than friends, and in Hunchback, Quasimodo has to watch someone else get the girl). I will concede that when you're just looking at happily-ever-afters, more films are on-model than not. Having said that, Frozen falls into the happily-ever-after category far more tidily than several of the films I had to shoehorn in there.

What's the point of all this? To illustrate right off the bat that Frozen's defenders are finding things to celebrate about the film that just don't hold up. Looking at it strictly by the numbers, Frozen conforms to the expected Disney model. And I know there's a twist in the way the love story is presented, but I'll get to that. Dealing strictly with the ''But there's no wedding!'' argument, I have to call bullshit.

One quick note before I continue-even though it's technically a Pixar film, I'll be counting Brave from this point on, since Merida has been officially inducted into the Disney Princess lineup.

The film passes the Bechdel test-no other Disney princess movie does that!

Why yes, yes it does. Granted, Elsa and Anna only actually have four conversations as adults, but three of them aren't about men, so yes, Frozen does pass the test.

You know which other Disney princess movies pass the Bechdel test? Most of them. Of the twelve films technically in the Disney Princess lineup (including Frozen), eleven of them pass. The only one that doesn't is Aladdin, and that's because Jasmine is the only speaking woman in the movie. Which, by the way, I'm not saying is a good thing; but whether Aladdin could have benefited from more female characters is another discussion entirely.

Frozen has two women in leading roles. It should pass the Bechdel test without effort; we shouldn't be surprised. What it lacks, however, that almost every other Disney princess movie has, is a roster of supporting female characters. Aside from Jasmine and Snow White (Snow White passes the Bechdel test by virtue of one conversation with the Queen near the end of the movie), all of Disney's heroines have strong female influences in their stories. Aurora is raised by three fairies; Belle befriends both Mrs Potts and her wardrobe; Pocahontas' best friend is another young woman and her strongest guiding influence is Grandmother Willow; even Mulan, who spends most of her movie solely in the company of men, begins the story surrounded by women. In Brave, Merida barely interacts with any male characters at all.

I understand the nature of adaptation: characters change; some are cut and others are added; some are combined and others separated out. But-generally speaking, at least-it isn't Disney's habit to remove female characters from the source material in their adaptations. Particularly in the princess movies, young girls (and their mothers) make up such a huge slice of the target demographic-and therefore the box-office and merchandising profit-that diminishing the roles of the female supporting characters or switching them out for men would be an idiotic marketing decision. And, while I'm not suggesting that marketing is more important than strong narrative, in this case it does work in Disney's storytelling favour, providing a rich roster of maternal characters like Mrs Potts and Grandmother Willow. Remember that Disney heroines typically exist in extremely patriarchal environments, so inundating their narratives with ''strong'' women would seriously undermine their ongoing theme of subverting the assignations of those societies.

Which leads me neatly back to Frozen, because Frozen's setting is not explicity patriarchal. I don't know that having a queen instead of a king is necessarily normal in the world of Frozen, but Elsa's coronation certainly isn't treated as any kind of aberration. Women have enough respect and agency in this world that no one particularly comments on Arendelle's being ruled by a woman. No one speculates about whom she's going to marry or how many sons she's going to bear; for once, in fact, it's the man (Hans) who has to marry into royalty to have any real power.

I'm not saying that I disapprove of adaptation, or that I think that Disney generally takes too many liberties when adapting stories. Hell, I love what they did with Hamlet. But the original story of The Snow Queen has strong female character after strong female character, from the grandmother who tells Gerda (the original story's Anna) stories of the Snow Queen, to the Robber Girl who wants to be Gerda's friend, to the Princess who-get this-can't find a suitor because she refuses to marry a man who can't keep up with her intellectually. It's too many characters for one Disney film, with far too many subplots and intersecting storylines, but it also really begs the question ...for what was clearly supposed to be its most feminist animated film ever, adapted into one of its least patriarchal settings, why would Disney replace this entire lineup of interesting female characters with men?

Elsa and Anna might be two female characters in leading roles, but they're also the only women in the whole film. The original story doesn't so much pass the Bechdel test as run rings around it; Frozen barely scrapes a pass. And, while there's definitely a marketing logic behind having some fun male supporting roles the boys can enjoy, there is nothing to praise in replacing every single female supporting role from the story with a male analogue. Why did Anna need a male companion, if both plucky comic relief characters were male? Or vice-versa: female reindeer grow antlers, so Sven could have been a female without even changing the aesthetic.

Narratively speaking, I think Frozen made wrong choice after wrong choice, and I've no great love for any of the characters, so I can't honestly say how I'd have fixed it without changing the story entirely. But I can say that praising the film for passing the Bechdel test is meaningless in the face of 1) the number of its predecessors that also pass just as comfortably, and 2) the fantastic supporting cast of female characters from the original story that Disney cast aside in favour of surrounding Elsa and Anna with men. The only reason to give Anna a male travelling companion-that I can think of-is to uphold the traditional love story that everyone is so convinced the film subverts.

It's a Disney movie with two strong female characters-arguably two female protagonists!

No it isn't. This is where I really start to take issue with all the effusive praise being heaped on the film. I'll address the ''two protagonist'' issue a few paragraphs from now-trust me, it's more relevant there-but I really worry about this pervasive conviction that Anna and Elsa are ''strong'' characters. Leaving aside for the moment all the women that Frozen could have included (see above), let's take a good, hard look at both main characters, beginning with Anna.

Quick, what defines Anna? She's beautiful, in a gives-Barbie-body-dysmorphia kind of way. That's par for the course with Disney heroines, except for Merida and Mulan. She's clumsy, which would be endearing except that it seems to be the de facto flaw for heroines who aren't fully-developed enough to have a real flaw-and yes, this would be the point where I compare Frozen to Twilight. Anna's clumsiness doesn't move the plot. It doesn't affect the outcome of ...anything, really. It isn't something she has to overcome-like Mulan does-thereby displaying strength or determination. It's just a trait she has so that we will find her more approachable: a cold, hard, marketing decision.

What else does Anna have going for her? She isn't intelligent, no matter how many words she can spit out per minute. If she were, she wouldn't rush into an engagement with Hans, nor-for that matter-leave a man she barely knows in charge of her kingdom while she rides out in the snow without a coat. She's certainly self-absorbed, using the first opportunity to make Elsa's coronation all about her; and she's vain, believing absolutely in her ability to talk some sense into Elsa despite having had no relationship with her sister for what looks like roughly ten years. She has no awareness of her surroundings (riding out in the snow without a coat), no awareness of her own limitations (the cringe-inducing mountain climbing episode), and no awareness of the consequences of her actions (provoking Elsa not once, but twice). She's outspoken, yes, but she's also rude; she's condescending towards Kristoff and belligerent towards her sister; and she has no ambition beyond finding her one true love-more on that below.

When it comes to women I'd look up to or consider role models, especially for young girls, Anna ranks somewhere around Mean Girls' Karen Smith, and certainly well below bookish Belle, feisty Merida, determined Tiana or even kindly Cinderella. I certainly didn't spend the movie thinking how approachable Anna was, as so many other young women breathlessly profess to; I spent it wanting to grab her by the pigtails, give her a good shake, and tell her to wake up and smell the snowflakes.

Despite her Oscar-bait identity-claiming power anthem, Elsa is no better than her younger sister. She may even be worse. We'll deal with her crippling self-repression later, because that isn't actually her fault, but this is a woman who steadfastly refuses to accept any help offered to her. Her sister spends the better part of ten years trying to reach out to her (admittedly misguidedly), and Elsa shuts herself away so steadfastly a psychiatrist might call it pathological. She's an absolute mess of characterological self-blame and avoidance, and she deals with her issues by speed-skating away from them.

Running from her problems once is one thing. Elsa is far from the first Disney character to believe-even correctly-that s/he has done something terrible, and to attempt to outrun the consequences. But Simba, faced with the reality of the harm he has inflicted on the Pride Lands, makes the conscious, independent choice to turn around and set things right, while Quasimodo literally brings the walls of Notre Dame down around him to right his wrongs. Faced with her misdeeds, Elsa sets a golem on her sister and has to be dragged back to Arendelle in chains when she's knocked unconscious by her own chandelier. This is not a strong woman. This is a frightened, repressed, vulnerable woman who starts running at the beginning of the movie and doesn't stop until her sister literally turns to ice in front of her.

So what does Elsa have going for her? She's beautiful, like her sister-unsurprising, since they're the same woman with different hairdos. And at the very end, I suppose she does warm up a little (pun definitely intended). But her redemption is an unearned arc. She never says-never even intimates-that she wants to right the wrong she's done. She just wants to run from it. She's more intelligent than Anna, but only barely; she's anti-social; and she also has little to no awareness of the consequences of her actions: especially troubling since even a small amount of ice-conjuring probably messes the local eco-system up pretty badly.

There's an ongoing problem, I think, with ''strong female character'' being made synonymous with ''any fictional woman who isn't just window dressing''. There's a whole argument to be made about why the phrase ''strong female character'' is a problem in and of itself-after all, do you ever hear a writer set out specifically to write a ''strong male character''?-but I think that that's what going on with Frozen. Because both characters are arguably leads, and neither is reduced to talking production design, we are conditioned to see them both as ''strong'', whether or not they actually are. Frozen certainly has two female characters. It even arguably has two lead female characters. But it certainly doesn't have two strong female characters, and two out of three just isn't enough to justify all the praise.

Both women have clearly defined goals, that aren't just ''I want to find true love!''

And this is where I wonder whether I was watching the same movie as everyone else. Let's start with Elsa, for once. What is her goal? Does she even have one?

It can't be ''be accepted for who I am'', because she isolates herself completely; it isn't ''learn to control my power'', because she never studies her power so much as she runs away from what destabilises her. She never expresses any particular wish to be closer to Anna, nor does she lust after power or eternal winter. She leaves her kingdom far too quickly to want to do right by her subjects, so she can't want to be a good queen. If my life depended on intentifying Elsa's motive, I'd probably settle on ''live free from fear'', but that's starting to get pretty abstract for a Disney princess.

There's a particular pattern that I've noticed in Disney animated features. Disney princesses state what they want, usually very early in the film, and they tend to get it. Belle wants to escape her provincial life, and that's exactly what she does. Rapunzel wants to figure out what the glowing lights mean, and again: that's exactly what she does, discovering her whole hidden history in the process. Mulan wants to bring honour to her family, and she ends up bringing honour to the whole of China. Even Ariel, who of all the recent Disney princesses is the most criticised for a lack of ambition outside of love, wants to experience life as a human long before she meets Eric. Tiana wants a restaurant, Pocahontas wants to choose her own path, Jasmine wants to escape the confines of patriarchal law; the list goes on. And the men in these stories? They're the bonus prizes.

Think about your typical male-dominated action or adventure movie. The man sets out to save the kingdom, find the Holy Grail, slay the dragon, or whatever it is that drives his story. The hero accomplishes his goal, and it's usually pretty much a given that he finds love along the way. The social contract in a male-driven movie is that he is offered a woman as a bonus prize; no matter how aloof or damaged or resistant she is, the hero will win her over and claim her love. It's a shitty social contract, but that's what we expect it to be.

In Disney princess movies, that social contract is turned precisely on its head. The princess starts her story with a goal or dream. She undergoes trials and tests in pursuit of that dream, usually making new friends along the way. Once she achieves that dream-which she invariably does-she is usually given a prince as a reward (notable exceptions include Pocahontas and Brave), the prince more often than not being one of the friends she has met along the way.

If it sounds simplistic, it's because it is. No matter how much Disney animated films may appeal to adults, their target demographic is still children-and usually children under the age of twelve. For stories that are essentially morality tales, simplicity is a benefit. So the heroine states her goal within the first fifteen minutes of the movie, usually in the Menken-styled ''I want'' song, and that means that everyone in the audience knows precisely when to cheer at the end of the movie. Ariel wants to be human, so we cheer when Triton gives her her legs; Mulan wants to bring honour to her family, so we cheer when she returns home with the Emperor's gifts; Belle wants ''adventure in the great, wide somewhere'', and oh boy, does she get what she asked for. Pocahontas chooses her own path, Merida changes her fate, Tiana gets her restaurant, and so on.

Just like every other Disney princess, Anna states what she wants very early on. She wants to find ''the one''. And, just like every other Disney princess, she gets exactly what she wants. Her renewed relationship with Elsa; the castle gates being opened for good: these are the bonus prizes. Anna's real goal is true love. We know this for certain because, just like every Disney heroine before her, she helpfully tells us so in her first scene as an adult. Her ''I want'' song is all about finding a man and falling in love; she doesn't even mention her sister. As far as I can tell, she can't get away from Elsa and everything she represents fast enough.

But ...but ...Anna's grown up in isolation: of course her priorities are a bit messed up!

No need to get defensive about it, but yes, a little social awkwardness is probably to be expected for a girl who's lived in almost total isolation for ...three years. Yes, I'm extrapolating a little here: we certainly don't see Anna interact with anyone aside from her sister and parents until Elsa's coronation. But think about it logically. After the ice incident as children, Elsa may be isolated-both by her parents and by her own fear-but there's no reason for the King and Queen to isolate Anna too. They almost certainly still have official functions to attend to: we know from Elsa's coronation that the monarch is responsible for negotiating trade arrangements and treaties, so it would be extremely irresponsible for the King and Queen to hole themselves away like their daughter. Seeing what enforced isolation does to Elsa, does it seem likely that they would force the same upon their non-powered daughter?

It seems far more likely that Anna is only shut inside the castle long-term after her parents die, and text on the screen tells us explicitly that only three years pass between that and Elsa's coronation. Three long, lonely, boring years, I'm sure, but three years that seem to send Anna far further off-balance than lifetimes of isolation do to other Disney princesses. Unlike, say, Rapunzel, Jasmine or Aurora, Anna has spent some fifteen years of her life in relative normality, presumably experiencing culture, friendships, and perhaps even her first crush in that time: all the things a normal aristocratic teenager could expect to experience. And even in the three years spent shut in the castle, what about the servants? Given Anna's natural boisterousness, unless Arendelle is really classist, I find it hard to imagine she didn't interact with and even make friends among the castle staff, whom we know exist because frankly it's far more believable than Elsa and Anna doing their own laundry.

Jasmine escapes a lifetime of solitude in the palace eager to explore the reality of Agrabah. Rapunzel spends eighteen years alone in a tower and leaves to fight her way to her own history armed with magic hair and a skillet. Even Belle compensates for her social isolation by reading voraciously about the wide world around her. Anna has to endure three years of-at worst-relative isolation, and she emerges so desperate for love that she gets engaged to literally the first young man she meets. It isn't so much ridiculous because it's a stupid thing to do; it's ridiculous because a girl that obsessed with finding love should already have a crush on a cute stable-boy.